by Ben Lerner

Granta

2012

Leaving the Atocha Station really did not do much for me. It's a short literary novel about an aspiring poet. The narrator is a whiny White American guy spending his first year out of undergrad in Spain on a fellowship.

The narrator lies about himself compulsively. He tries to act enigmatic in the hope that people will fill in his gaps with their imaginations, and that their image of him will be better than the truth. He writes a little poetry, takes a lot of drugs, and spends most of his time trying to impress two different Spanish women. He does want to get in their pants, but I think it's even more important to him that they think he's a cool, mysterious genius.

He worries that he's a fraud, and honestly, it seems like he is.

I think one appeal of the books for writers is maybe recognizing themselves or their colleagues when they were just out of college and felt like imposters. Another appeal probably is the ideas about poetry that the author, Ben Lerner, gives the guy. He thinks a lot about how poetry fails to emotionally affect him and how what does emotionally affect him is his lack of response to this art that other people seem affected by. Yes, there's a parallel between what he says about poetry and how he tries to portray himself as interesting via absences and blank spaces he hopes others will fill with their own meanings.

The narrator's trip to Spain coincides with the 2004 Madrid transit bombing, which affects the country somewhat like the way 9/11 affected the US.

The book's two saving graces are that Lerner doesn't defend the narrator and shows that he's aware of the guy's self-delusions, so at least I get to feel my contempt without encountering defensiveness, and also it's pretty short.

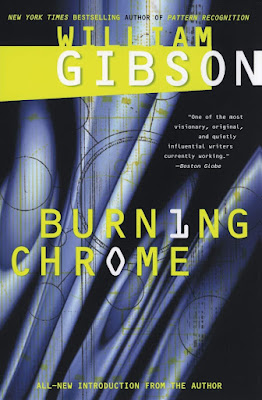

I've seen a lot of praise for this one, and like I said, it might appeal to professional writers more than it appealed to me, but I still think it's over-praised. It also has a really cool looking cover that somehow led me to expect something different than what I got.